{width="4.90625in"

height="2.90625in"}

{width="4.90625in"

height="2.90625in"}Conda install packagename

Conda update packagename

Pip install packagename (use conda if you can for conda environments)

Objects have a type, and a set of methods that run on that type.

Import somemodule

somemodule.a(d, e)

Or:

From somemodule import a

a(d, e)

Most are mutable (lists, dicts, numpy arrays, classes).

Strings and tuples are immutable.

Str (unicode), bytes, float, bool, int.

Named arguments:

"hello {name}".format(name = "Jeremy")

"cost is {cost:6.3f}.format(cost = "230.3498", ) -> 230.35

# default arguments

print("Hello {}, your balance is {}.".format("Adam", 230.2346))

# positional arguments

print("Hello {0}, your balance is {1}.".format("Adam", 230.2346))

# keyword arguments

print("Hello {name}, your balance is {blc}.".format(name="Adam", blc=230.2346))

# mixed arguments

print("Hello {0}, your balance is {blc}.".format("Adam", blc=230.2346))

# arguments with index

"start: {}".format(Df2.shape[0])

The join() is a string method which returns a string concatenated with the elements of an iterable.

Concatenate with +

print('str1 + str2 = ', str1 + str2)

String operations

>>> "PrOgRaMiZ".lower()

'programiz'

>>> "PrOgRaMiZ".upper()

'PROGRAMIZ'

>>> "This will split all words into a list".split()

['This', 'will', 'split', 'all', 'words', 'into',

'a', 'list']

>>> ' '.join(['This', 'will', 'join', 'all',

'words', 'into', 'a', 'string'])

'This will join all words into a string'

>>> 'Happy New Year'.find('ew')

7

>>> 'Happy New Year'.replace('Happy','Brilliant')

'Brilliant New Year'

A variable takes on the type of the value assigned.

Everything is an object in Python, and any object can be assigned to a variable.

Like in other programming languages, objects can have state (attributes or values) and behavior (methods).

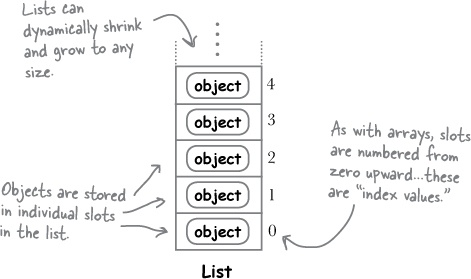

List: an ordered mutable collection of objects. Not predefined size, any objects, has sequence.

{width="4.90625in"

height="2.90625in"}

{width="4.90625in"

height="2.90625in"}

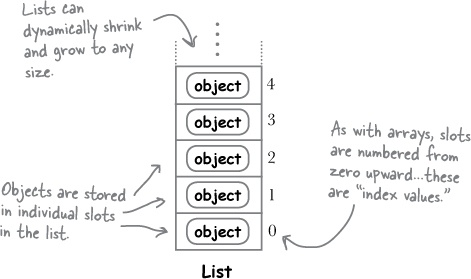

Tuple: an ordered immutable collection of objects. Like a constant list.

{width="4.395833333333333in"

height="3.0520833333333335in"}

{width="4.395833333333333in"

height="3.0520833333333335in"}

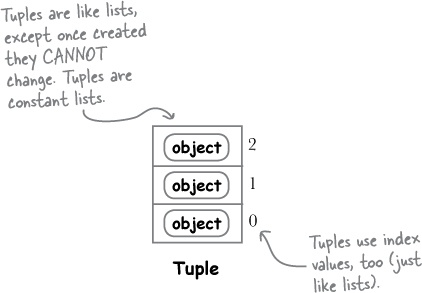

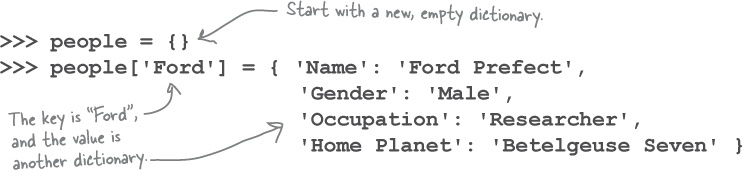

Dictionary: an unordered set of key/value pairs

{width="4.458333333333333in"

height="3.3229166666666665in"}

{width="4.458333333333333in"

height="3.3229166666666665in"}

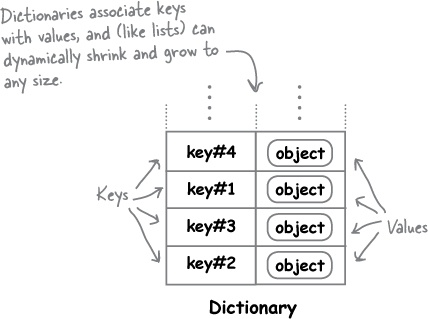

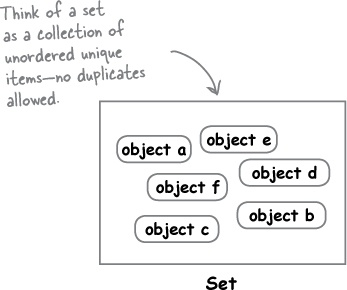

Set: an unordered set of unique objects

{width="3.6145833333333335in"

height="3.0208333333333335in"}

{width="3.6145833333333335in"

height="3.0208333333333335in"}

Lists: [square brackets, comma separated objects]. Can do list of lists.

Append(object) to add object

remove(object) to remove

pop(index) to remove on index (or last) and returns it

list1.extend(list2) to add list2 to list1

list.insert(index to insert before, object to insert)

for name / value pairs. Like a map. Order not preserved. Load using curly braces, with a colon for the key. Access with square brackets.

Person3 = {'Name': 'Jremy',

'Gender': 'M'}

Lookup with square brackets: person3['Gender']

Check out this for the parser interpretation: https://docs.python.org/3/reference/lexical_analysis.html#operators

For loop only iterates over the keys. Use sorted function e.g. for k in sorted(dictionary). Sorted returns an ordered copy, doesn't change the original.

Items method with for loop is best way to get the data.

e.g. for k, v in sorted(found.items)):

print(k, 'was found', v, 'times')

Dictionary keys must be inititialised. So check membership with 'in'. Or set the default

Sets: like a list with unique values, curly braces, faster than list, can use set operators. Curly braces look like dictionary, but no colons. Can use set logic (union, difference, intersection)

Tuples: like a list but immutable. Round brackets. Cant have a single object in a tuple unless add a comma.

Use type(object) to see if it's a list / dictionary etc.

Often have e.g. dictionary of dictionaries.

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.4361111111111111in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.4361111111111111in"}

Access with people['Ford']['Gender']. Print with pprint

Modules are a collection of functions in a file.

Library is multiple modules.

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.3444444444444446in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.3444444444444446in"}

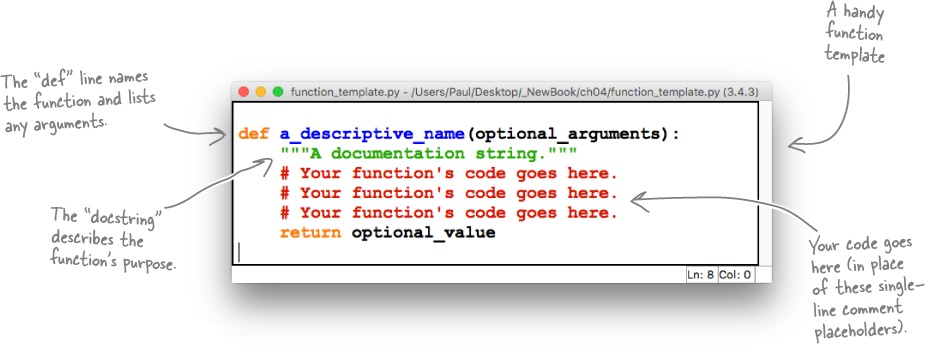

Functions in a class are methods.

Doesn't force you to specify the return type, just objects.

String delimiters: ' and " are the same.

Doc strings are """, can span multiple lines. PEP8 is best practice format. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/.

Pass args, return a single object - but this could be a data structure.

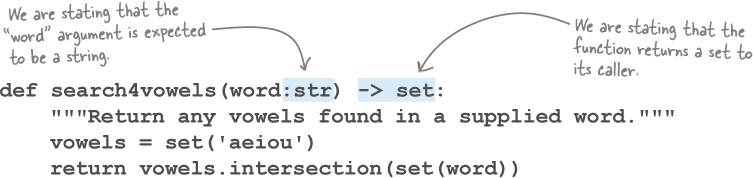

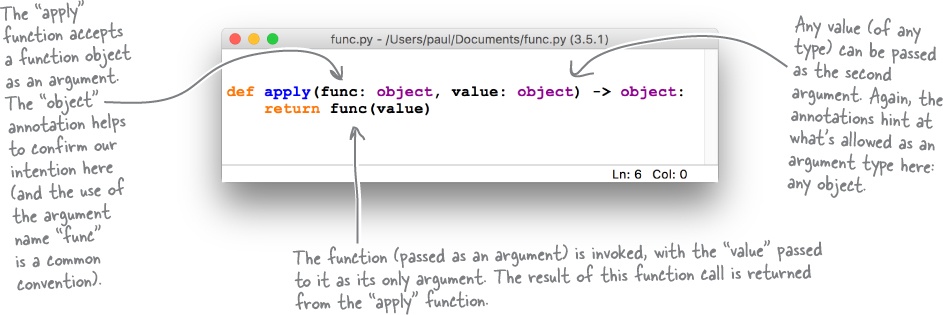

Function annotations:

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.4819444444444445in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.4819444444444445in"}

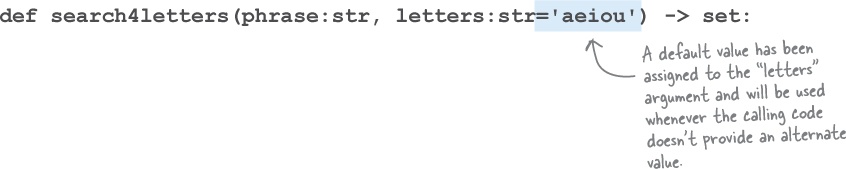

Python doesn't check the type of parameters passed to a function call, or the type of return values. Everything's an object. Annotations just for documentation. Visible with help BIF.

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.2520833333333334in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.2520833333333334in"}

Modules

Import a module, but interpreter assumes module is on the search path. Import error if not. Cant specify full path. This is hard! Looks in

Current working directory

Interpreters site package locations

Standard library locations

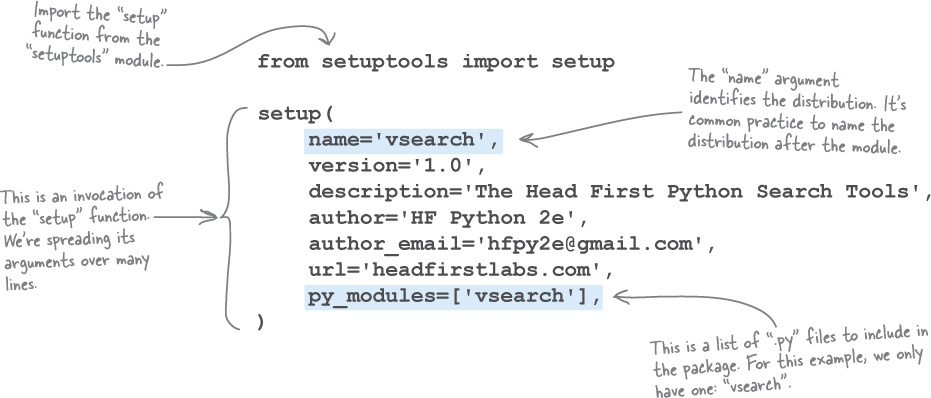

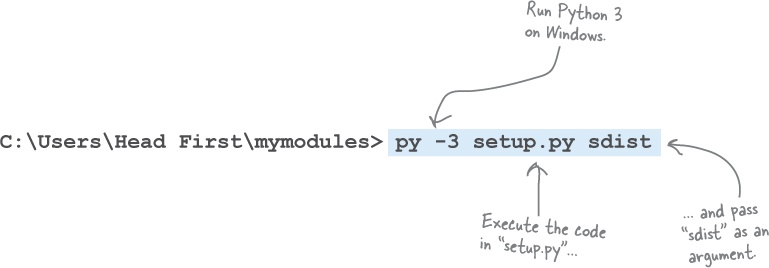

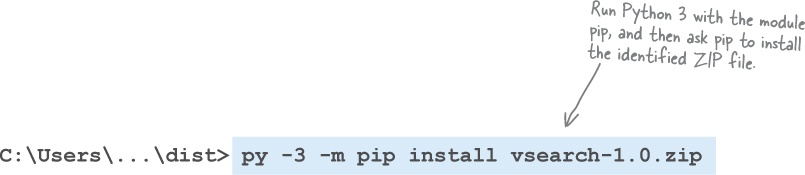

Setuptools module in standard library has the tools to add / remove from site packages.

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.6798611111111112in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.6798611111111112in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.1847222222222222in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.1847222222222222in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.3625in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.3625in"}

Can share packages via PyPI (python package index). https://pypi.python.org/pypi.

Here's the kicker: both Tom and Sarah are right. Depending on the situation, Python's function argument semantics support both call-by-value and call-by-reference.

Recall once again that variables in Python aren't variables as we are used to thinking about them in other programming languages; variables are object references. It is useful to think of the value stored in the variable as being the memory address of the value, not its actual value. It's this memory address that's passed into a function, not the actual value. This means that Python's functions support what's more correctly called by-object-reference call semantics.

Based on the type of the object referred to, the actual call semantics that apply at any point in time can differ. So, how come in Tom's and Sarah's functions the arguments appeared to conform to by-value and by-reference call semantics? First off, they didn't---they only appeared to. What actually happens is that the interpreter looks at the type of the value referred to by the object reference (the memory address) and, if the variable refers to a mutable value, call-by-reference semantics apply. If the type of the data referred to is immutable, call-by- value semantics kick in. Consider now what this means for our data.

Lists, dictionaries, and sets (being mutable) are always passed into a function by reference--- any changes made to the variable's data structure within the function's suite are reflected in the calling code. The data is mutable, after all.

Strings, integers, and tuples (being immutable) are always passed into a function by value--- any changes to the variable within the function are private to the function and are not reflected in the calling code. As the data is immutable, it cannot change.

Testing framework: pytest, and pytest plugins.

Pep8 plugin can test for compliance with PEP8.

Install pytest with pip

Summary so far:

BULLET POINTS

IDLE, Python's built-in IDE, is used to experiment with and execute Python code, either as single-statement snippets or as larger multistatement programs written within IDLE's text editor. As well as using IDLE, you ran a file of Python code directly from your operating system's command line, using the py -3 command (on Windows) or python3 (on everything else).

You've learned how Python supports single-value data items, such as integers and strings, as well as the booleans True and False.

You've explored use cases for the four built-in data structures: lists, dictionaries, sets, and tuples. You know that you can create complex data structures by combining these four built-ins in any number of ways.

You've used a collection of Python statements, including if, elif, else, return, for, from, and import.

You know that Python provides a rich standard library, and you've seen the following modules in action: datetime, random, sys, os, time, html, pprint, setuptools, and pip.

As well as the standard library, Python comes with a handy collection of built-in functions, known as the BIFs. Here are some of the BIFs you've worked with: print, dir, help, range, list, len, input, sorted, dict, set, tuple, and type.

Python supports all the usual operators, and then some. Those you've already seen include: in, not in, +, -, = (assignment), ==(equality), +=, and *.

As well as supporting the square bracket notation for working with items in a sequence (i.e., []), Python extends the notation to support slices, which allow you to specify start, stop, and step values.

You've learned how to create your own custom functions in Python, using the def statement. Python functions can optionally accept any number of arguments as well as return a value.

Although it's possible to enclose strings in either single or double quotes, the Python conventions (documented in PEP 8) suggest picking one style and sticking to it. For this book, we've decided to enclose all of our strings within single quotes, unless the string we're quoting itself contains a single quote character, in which case we'll use double quotes (as a one-off, special case).

Triple-quoted strings are also supported, and you've seen how they are used to add docstrings to your custom functions.

You learned that you can group related functions into modules. Modules form the basis of the code reuse mechanism in Python, and you've seen how the pip module (included in the standard library) lets you consistently manage your module installations.

Speaking of things working in a consistent manner, you learned that in Python everything is an object, which ensures---as much as possible---that everything works just as you expect it to. This concept really pays off when you start to define your own custom objects using classes, which we'll show you how to do in a later chapter.

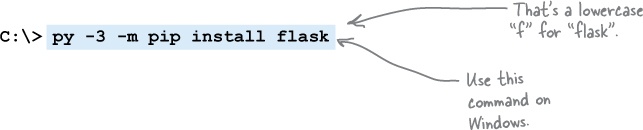

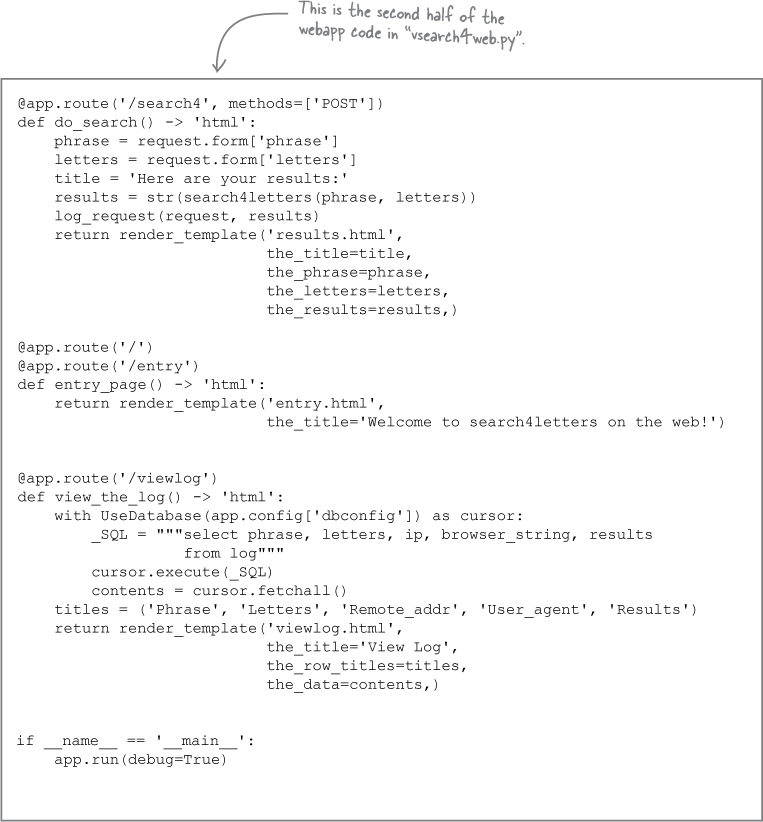

Flask is a small web application framework.

Django is a much bigger one with good admin facilities, but overkill for this.

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.2673611111111112in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.2673611111111112in"}

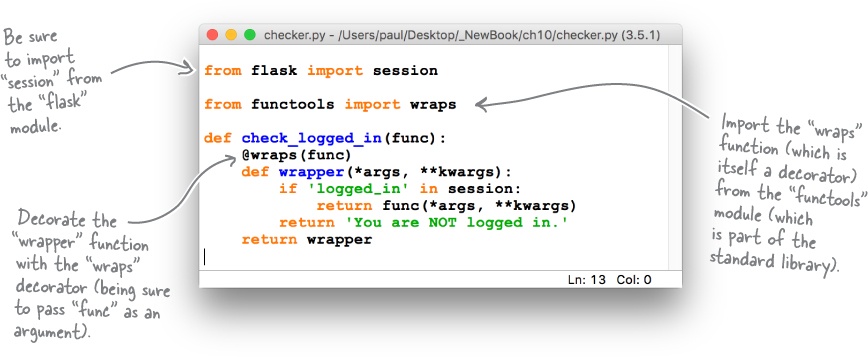

Function decorator adjusts the behaviour of a function without needing to change code. Function is decorated. Take existing code and augment it with additional behaviour.

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.6805555555555556in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.6805555555555556in"}

Q: I'm a little confused by the 127.0.0.1 and: 5000 parts of the URL used to access the webapp. What's the deal with those?

A: At the moment, you're testing your webapp on your computer, which---because it's connected to the Internet---has its own unique IP address. Despite this fact, Flask doesn't use your IP address and instead connects its test web server to the Internet's loopback address: 127.0.0.1, also commonly known as localhost. Both are shorthand for "my computer, no matter what its actual IP address is." For your web browser (also on your computer) to communicate with your Flask web server, you need to specify the address that is running your webapp, namely:127.0.0.1. This is a standard IP address reserved for this exact purpose.

The :5000 part of the URL identifies the protocol port number your web server is running on.

Typically, web servers run on protocol port 80, which is an Internet standard, and as such, doesn't need to be specified. You could type oreilly.com:80 into your browser's address bar and it would work, but nobody does, as oreilly.com alone is sufficient (as the :80 is assumed).

When you're building a webapp, it's very rare to test on protocol port 80 (as that's reserved for production servers), so most web frameworks choose another port to run on. 8080 is a popular choice for this, but Flask uses 5000 as its test protocol port.

TEMPLATES UP CLOSE

{width="1.25in"

height="0.9479166666666666in"}

{width="1.25in"

height="0.9479166666666666in"}

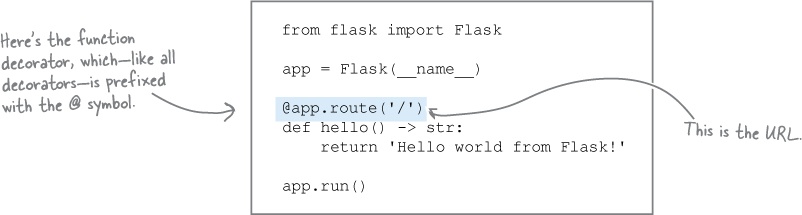

Template engines let programmers apply the object-oriented notions of inheritance and reuse to the production of textual data, such as web pages.

A website's look and feel can be defined in a top-level HTML template, known as the base template, which is then inherited from by other HTML pages. If you make a change to the base template, the change is then reflected in all the HTML pages that inherit from it.

The template engine shipped with Flask is called Jinja2, and it is both easy to use and powerful. It is not this book's intention to teach you all you need to know about Jinja2, so what appears on these two pages is---by necessity---both brief and to the point. For more details on what's possible with Jinja2, see:

http://jinja.pocoo.org/docs/dev/

Here's the base template we'll use for our webapp. In this file, called base.html, we put the HTML markup that we want all of our web pages to share. We also use some Jinja2-specific markup to indicate content that will be supplied when HTML pages inheriting from this one are rendered (i.e., prepared prior to delivery to a waiting web browser). Note that markup appearing between {{ and }}, as well as markup enclosed between {% and %}, is meant for the Jinja2 template engine: we've highlighted these cases to make them easy to spot:

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="3.0708333333333333in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="3.0708333333333333in"}

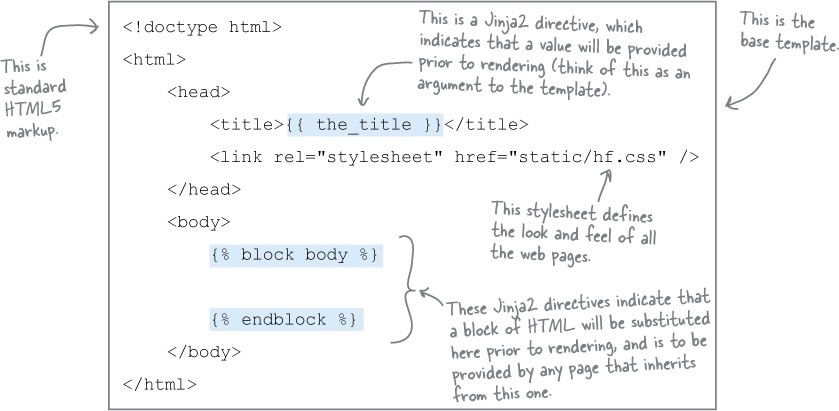

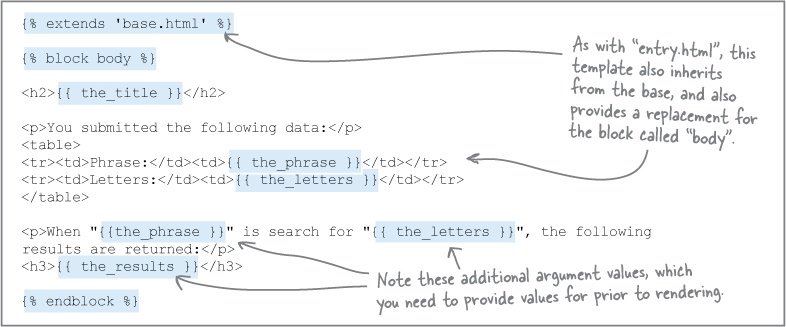

With the base template ready, we can inherit from it using Jinja2's extends directive. When we do, the HTML files that inherit need only provide the HTML for any named blocks in the base. In our case, we have only one named block: body.

Here's the markup for the first of our pages, which we are calling entry.html. This is markup for an HTML form that users can interact with in order to provide the value for phrase and letters expected by our webapp.

Note how the "boilerplate" HTML in the base template is not repeated in this file, as the extends directive includes this markup for us. All we need to do is provide the HTML that is specific to this file, and we do this by providing the markup within the Jinja2 block called body:

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.6479166666666667in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.6479166666666667in"}

And, finally, here's the markup for the results.html file, which is used to render the results of our search. This template inherits from the base template, too:

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.607638888888889in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.607638888888889in"}

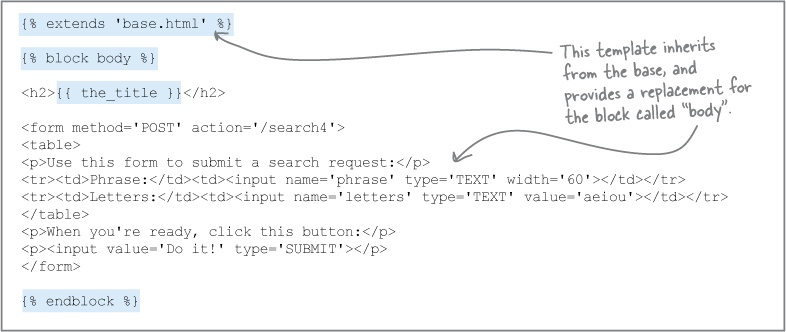

Debug mode for flask: automatically restarts webapp when code changed.

Used to prevent app.run being called when run on e.g. AWS, but is called when run locally.

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="0.9520833333333333in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="0.9520833333333333in"}

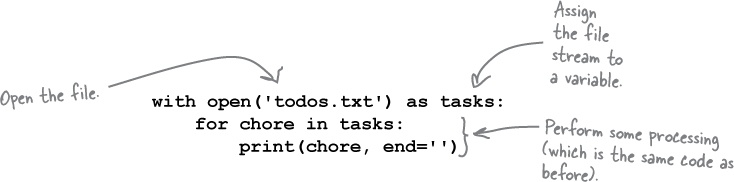

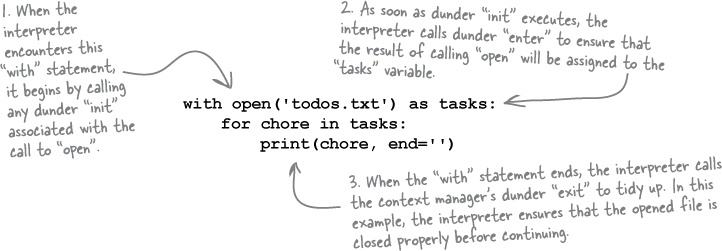

File open, operations, close

Better to use with:

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.5541666666666667in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.5541666666666667in"}

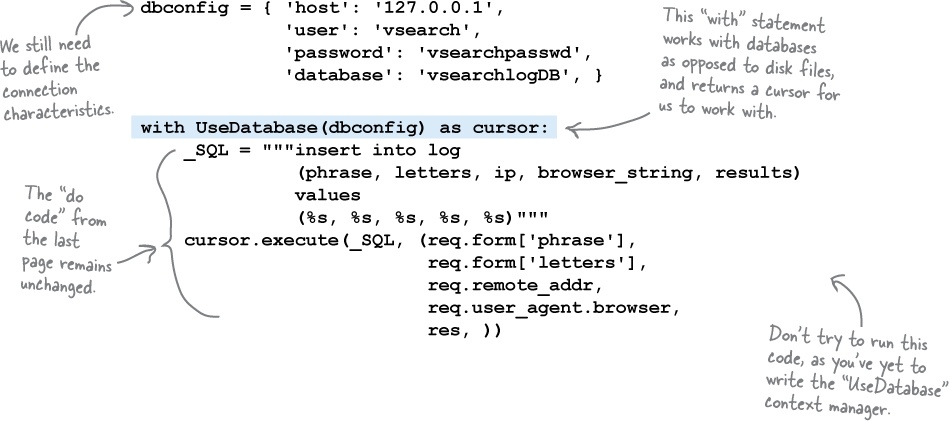

DB-API is standard library to talk to any sql database

Need a driver to connect.

MySQL owned by Oracle!

Standard stuff.

Use a context manager and "with" statement to manage initialisation, work and teardown in less statements

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.7805555555555554in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.7805555555555554in"}

Don't put import startements in a function or theyre exectured with every function call.

OO is optional

Can use with statement with or without a class, but class is better.

"Context management protocol" is needed with the with statement.

Class encapsulates behavior (ie implements a function, method) and state (variables, attributes)

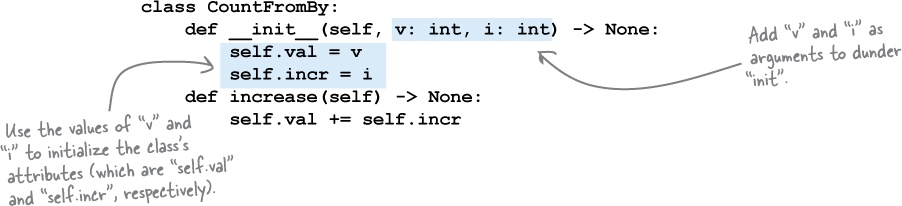

Create a class with

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.43125in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.43125in"}

Instantiate with

A = CountFromBy()

Looks like a function call. Functions should have lower case and underscores. Classes have Hungarian notation.

Methods always take (self) as the first argument (alias to the current object), but you don't pass this when calling methods.

Object construction handled by the optimiser. Use magic method __init__ to initialise. Dunder init. Other dunder methods are dunder eq for ==, dunder ge for > operator. Can overwrite these for a class. E.g. overwrite dunder repr for string representation of object.

Context manager means you can use the WITH statement to manage initiation and tear down.

Create a class, protocol says need to define 2 dunder magic methods: __enter__ and __exit__. Then you can use with..

Best to use __init__ also.

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.1791666666666667in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.1791666666666667in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="6.752777777777778in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="6.752777777777778in"}

Web requests are all stateless so independent, no memory. HTTP enforces this. Web apps can load and unload at the discretion of the server, so not practical to hold state. No global variables for web app state.

Sessions used instead. Flask web server implements this. Session like a layer of state. Add a cookie to the browser, link this to a session ID on the web server. Each user gets their own session, can store state on web app.

Decorators prefixed with @.

functions are objects with an ID. Just pass the name of the function as the argument.

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.09375in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.09375in"}

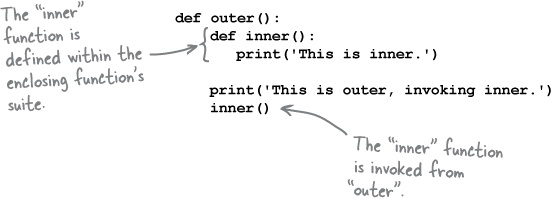

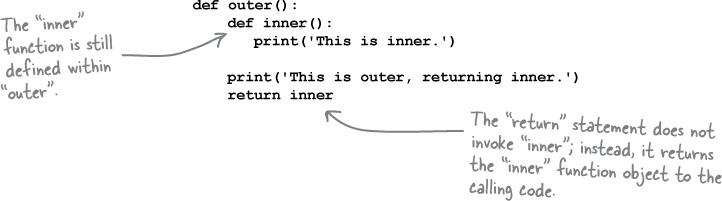

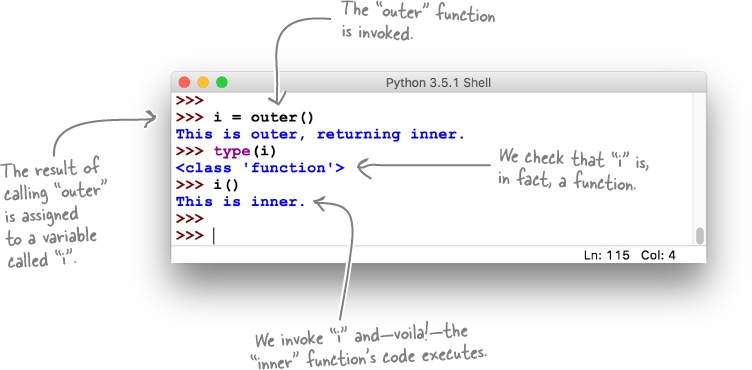

Code in a function can define another function. Can return the nested function.

{width="5.739583333333333in"

height="2.0625in"}

{width="5.739583333333333in"

height="2.0625in"}

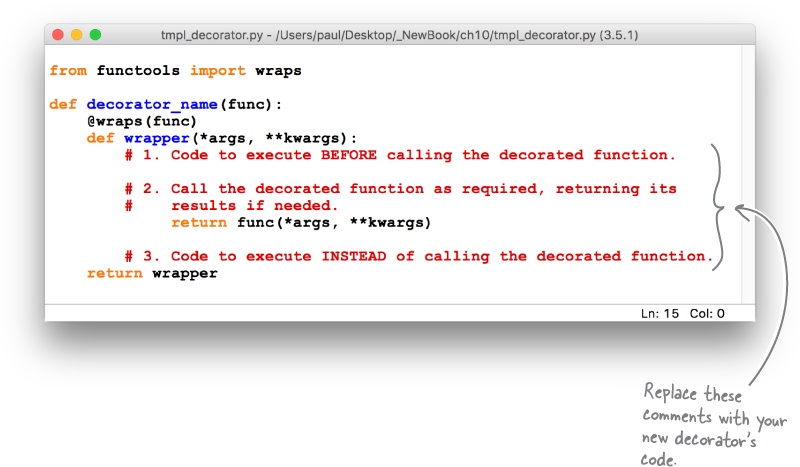

A more common usage of this technique arranges for the enclosing function to return the nested function as its value, using the return statement. This is what allows you to create a decorator.

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.7451388888888888in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="1.7451388888888888in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="3.0840277777777776in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="3.0840277777777776in"}

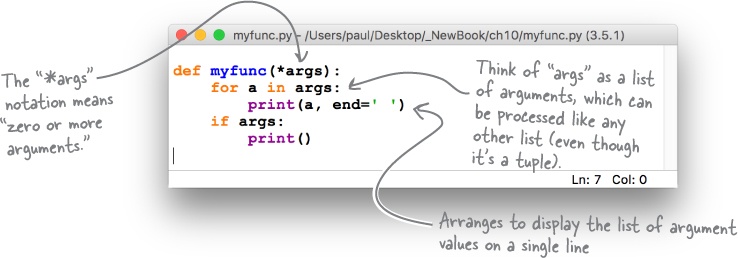

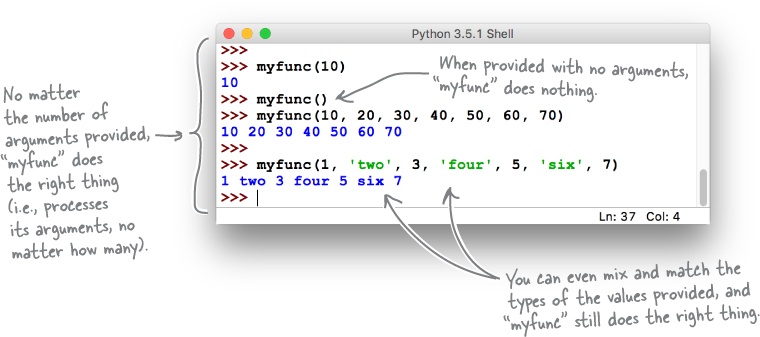

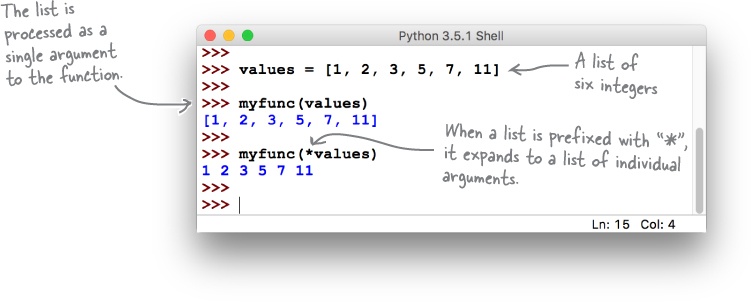

Python provides a special notation that allows you to specify that a function can take any number of arguments (where "any number" means "zero or more"). This notation uses the * character to represent any number, and is combined with an argument name (by convention, args is used) to specify that a function can accept an arbitrary list of arguments (even though *args is technically a tuple).

Think of * as meaning "expand to a list of values."

Here's a version of myfunc that uses this notation to accept any number of arguments when invoked. If any arguments are provided, myfunc prints their values to the screen:

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.1909722222222223in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.1909722222222223in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.779166666666667in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.779166666666667in"}

If you provide a list to myfunc as an argument, the list (despite potentially containing many values) is treated as one item (i.e., it's onelist). To instruct the interpreter to expand the list to behave as if each of the list's items were an individual argument, prefix the list's name with the * character when invoking the function.

Another short IDLE session demonstrates the difference using * can have:

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.5208333333333335in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.5208333333333335in"}

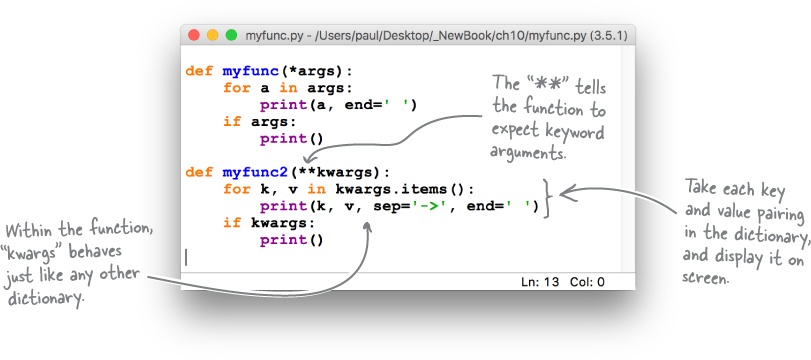

In addition to the * notation, Python also provides **, which expands to a collection of keyword arguments. Where * uses args as its variable name (by convention), ** uses kwargs, which is short for "keyword arguments." (Note: you can use names other than args and kwargs within this context, but very few Python programmers do.)

Think of ** as meaning "expand to a dictionary of keys and values."

Let's look at another function, called myfunc2, which accepts any number of keyword arguments:

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.782638888888889in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.782638888888889in"}

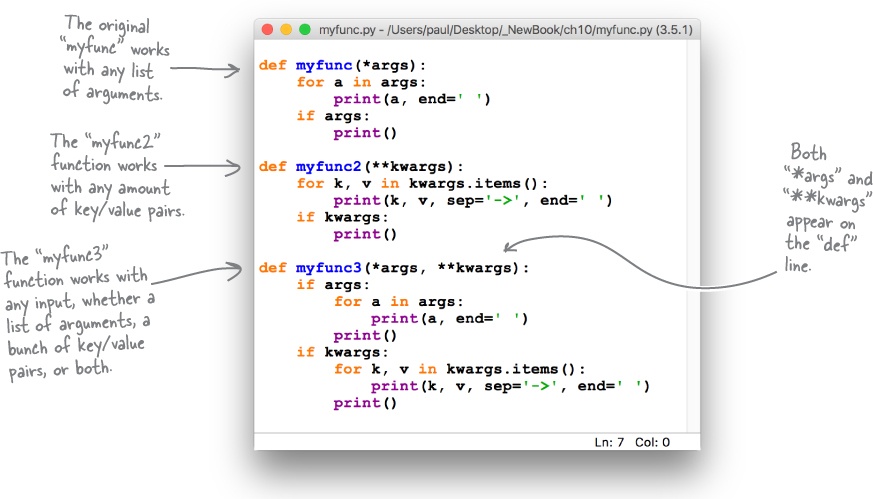

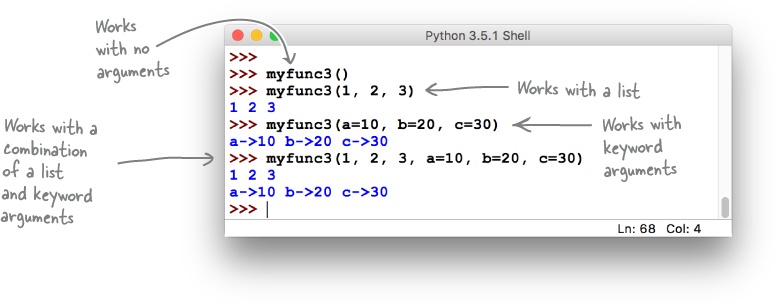

Here's a third version of myfunc (which goes by the shockingly imaginative name of myfunc3). This function accepts any list of arguments, any number of keyword arguments, or a combination of both:

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="3.582638888888889in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="3.582638888888889in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.46875in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.46875in"}

Decorator is a function

Decorator takes the decorated function as an argument

Decorator returns a new function

Decorator maintains the decorated functions signature

When creating your own decorators, always import, then use, the "functools" module's "wraps" function. (technical reasons in library).

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.577777777777778in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.577777777777778in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.509027777777778in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.509027777777778in"}

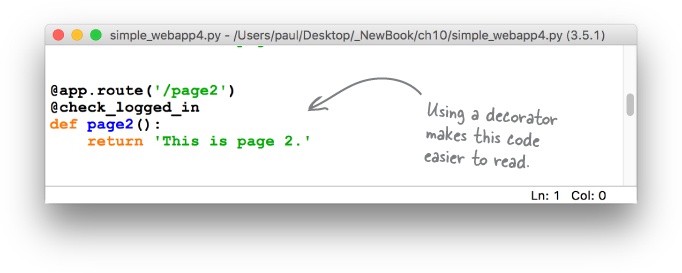

Note how the page2 function's code is only concerned with what it needs to do: display the /page2 content. In this example, the page2 code is a single, simple statement; it would be harder to read and understand if it also contained the logic required to check whether a user's browser is logged in or not. Using a decorator to separate out the login-checking code is a big win.

Decorators aren't freaky; they're fun.

This "logic abstraction" is one of the reasons the use of decorators is popular in Python. Another is that, if you think about it, in creating the check_logged_in decorator, you've managed to write code that augments an existing function with extra code, by changing the behavior of the existing function without changing its code.

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="3.6590277777777778in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="3.6590277777777778in"}

BULLET POINTS

{width="1.0208333333333333in"

height="0.7916666666666666in"}

{width="1.0208333333333333in"

height="0.7916666666666666in"}

When you need to store server-side state within a Flask webapp, use the session dictionary (and don't forget to set a hard-to-guess secret_key).

You can pass a function as an argument to another function. Using the function's name (without the parentheses) gives you a function object, which can be manipulated like any other variable.

When you use a function object as an argument to a function, you can have the receiving function invoke the passed-in function object by appending parentheses.

A function can be nested inside an enclosing function's suite (and is only visible within the enclosing scope).

In addition to accepting a function object as an argument, functions can return a nested function as a return value.

*args is shorthand for "expand to a list of items."

**kwargs is shorthand for "expand to a dictionary of keys and values." When you see "kw," think "keywords."

Both * and ** can also be used "on the way in," in that a list or keyword collection can be passed into a function as a single (expandable) argument.

Using (*args, **kwargs) as a function signature lets you create functions that accept any number and type of arguments.

Using the new function features from this chapter, you learned how to create a function decorator, which changes the behavior of an existing function without the need to change the function's actual code. This sounds freaky, but is quite a bit of fun (and is very useful, too).

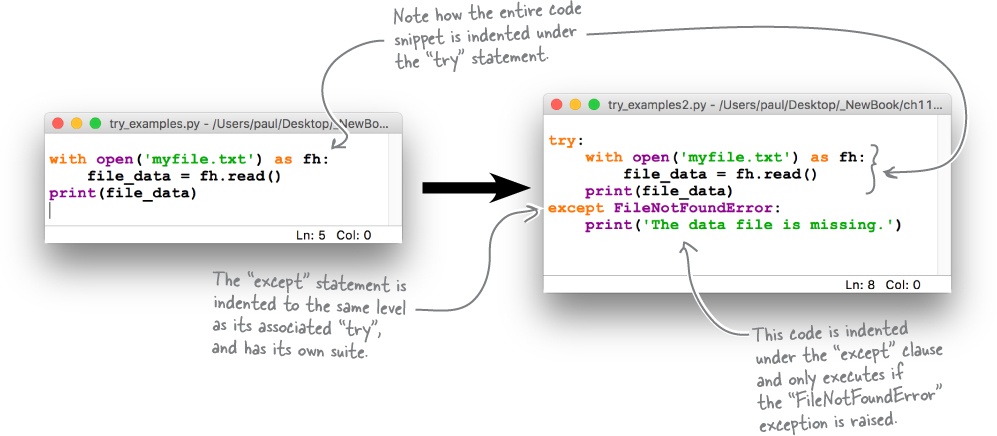

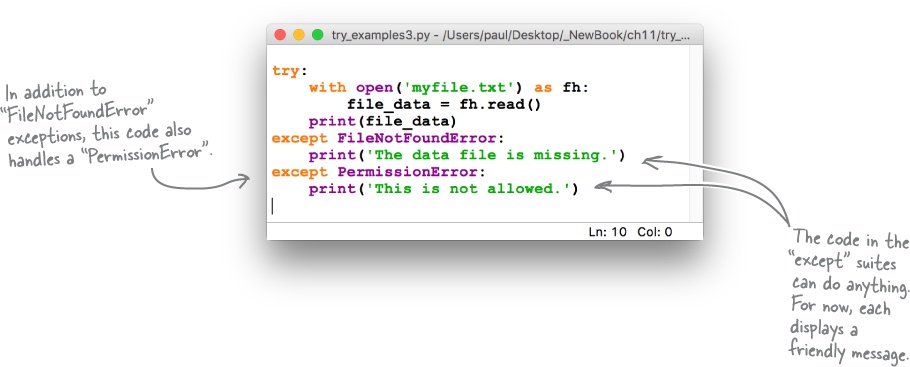

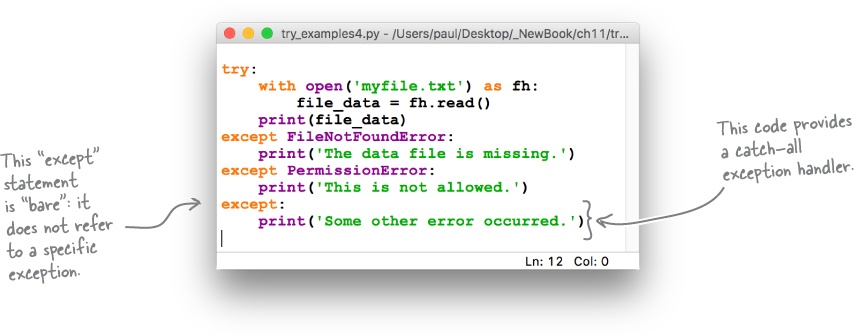

When a runtime error occurs, an exception is raised. If you ignore a raised exception it is referred to as uncaught, and the interpreter will terminate your code, then display a runtime error message (as shown in the example from the bottom of the last page). That said, raised exceptions can also be caught (i.e., dealt with) with the try statement. Note that it's not enough to catch runtime errors, you also have to decide what you're going to do next.

When a runtime error occurs, an exception is raised. If you ignore a raised exception it is referred to as uncaught, and the interpreter will terminate your code, then display a runtime error message (as shown in the example from the bottom of the last page). That said, raised exceptions can also be caught (i.e., dealt with) with the try statement. Note that it's not enough to catch runtime errors, you also have to decide what you're going to do next.

Perhaps you'll decide to deliberately ignore the raised exception, and keep going...with your fingers firmly crossed. Or maybe you'll try to run some other code in place of the code that crashed, and keep going. Or perhaps the best thing to do is to log the error before terminating your application as cleanly as possible. Whatever you decide to do, the try statement can help.

In its most basic form, the try statement allows you to react whenever the execution of your code results in a raised exception. To protect code with try, put the code within try's suite. If an exception occurs, the code in the try's suite terminates, and then the code in the try's except suite runs. The except suite is where you define what you want to happen next.

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.740972222222222in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.740972222222222in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.5277777777777777in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.5277777777777777in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

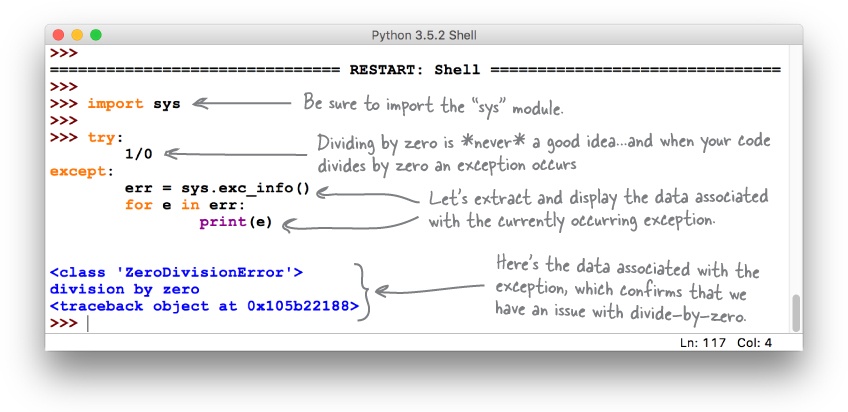

height="2.4590277777777776in"}The standard library comes with a module

called sys that provides access to the interpreter's internals (a set of

variables and functions available at runtime).

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.4590277777777776in"}The standard library comes with a module

called sys that provides access to the interpreter's internals (a set of

variables and functions available at runtime).

One such function is exc_info, which provides information on the

exception currently being handled. When invoked, exc_info returns a

three-valued tuple where the first value indicates the

exception's type, the second details the exception's value, and

the third contains a traceback object that provides access to the

traceback message (should you need it). When there is no currently

available exception, exc_info returns the Python null value for each of

the tuple values, which looks like this:(None, None,

None). {width="6.268055555555556in"

height="3.045138888888889in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="3.045138888888889in"}

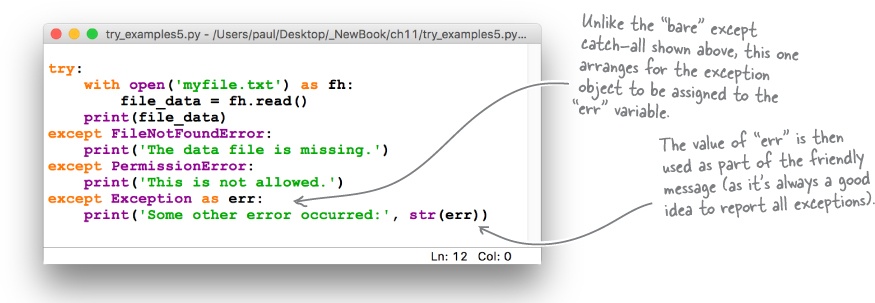

To make this (and your life) easier, Python extends the try/except syntax to make it convenient to get at the information returned by the sys.exc_info function, and it does this without you having to remember to import or interact with the sys module, nor wrangle with the tuple returned by the exc_info function.

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.1708333333333334in"}

{width="6.268055555555556in"

height="2.1708333333333334in"}

Create custom exceptions by extending the exception class